The Bank of England is expected to raise interest rates for a 13th consecutive time later as it tries to tackle rising prices.

Official data on Wednesday showed that inflation, the annual rate at which prices go up, was stuck at 8.7% in May.

That has made it more likely for the Bank to announce a rise in its benchmark rate from 4.5%.

Interest rates remain its primary tool to lower inflation, despite debate over its effectiveness.

Analysts say an increase to 4.75% is most likely, but a bigger increase to 5% remains a possibility, although one economist suggested such a rise could suggest the Bank has “completely lost control of inflation”.

Any such change would mean further pain for some homeowners, but it could benefit savers.

The Bank rate is already at its highest level for about 15 years, rising consistently since December 2021 in response to the soaring cost of living.

The theory is that raising interest rates makes it more expensive to borrow money, meaning people have less to spend, and so bringing down demand and therefore easing price rises.

A further rise is expected to be confirmed at 12:00 BST on Thursday after a meeting of the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee, which makes the decision independently of government.

Sir Charlie Bean, former deputy governor of the Bank of England for monetary policy, told the BBC’s Today programme that if he were on the committee he would “probably” vote for a 0.5% hike.

“The news since the last meeting has been unambiguously bad on an inflation front,” he said. “You’ve had two bad inflation releases and also the labour market release showed pay growth much stronger than they would have expected – you put all of that together and it’s a pretty clear signal it needs further rate increases.”

Sir Charlie said the question for the Bank was whether they wanted to do a “big step today, or a smaller step, but maybe indicating there will be more [rate rises] in the pipeline”.

Luke Hickmore, investment director at Abrdn, told the BBC there was a “large risk” of a 0.5% rise, but added that if the Bank did that it “may give the wrong message to the markets that it has completely lost control of inflation”.

In a speech he is due to give shortly after the decision is announced, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak will recommit to halving inflation by the end of the year and say he feels a “deep moral responsibility to make sure the money you earn holds its value”.

He is expected to tell a business event in south east England that he is “completely confident that if we hold our nerve” the target can be hit.

Labour’s shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves has criticised the government over the impact of rising rates on people with mortgages.

Ahead of the rate decision, she said: “Instead of squabbling over peerages and parties and ruling out any action on mortgages, the Tories should be taking responsibility and acting now.”

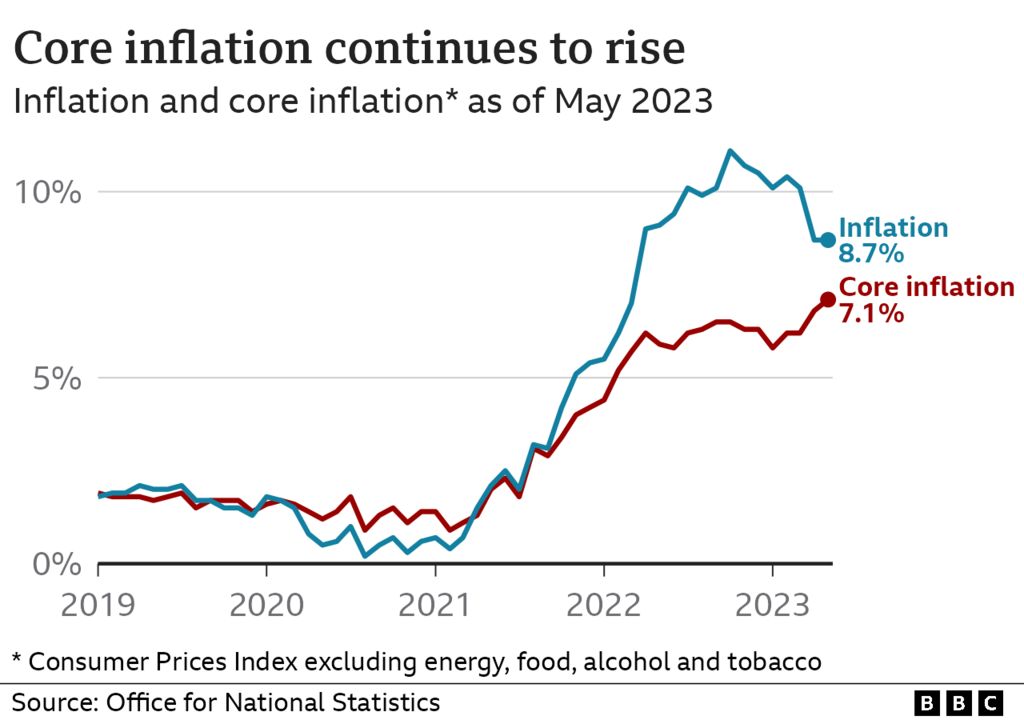

On Wednesday, the Office for National Statistics said that inflation was unchanged on the previous month at 8.7%. That was met with surprise by analysts who had expected it to fall.

The shock figure was driven by higher prices for flights and second-hand cars but supermarket food prices also continued to rise rapidly.

So-called “core” inflation, which strips out volatile factors such as direct energy and food prices, along with alcohol and tobacco prices, continued to rise last month at its fastest rate for 31 years.

Economists said this made the UK stand out from other countries such as the US and Germany where inflation is falling.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt appeared to back further interest rate rises saying it would not “hesitate in our resolve to support the Bank of England as it seeks to squeeze inflation out of our economy”.

The government’s target is to halve the inflation rate to 5% by the end of the year. The official, long-term target set for the Bank is 2%.

Rob Morgan, from investment firm Charles Stanley, said: “Getting the inflation genie back into the bottle is proving troublesome for the Bank of England.

“With price momentum continually running above expectations alongside strong wages data, the Bank has no choice but to continue on a path of raising interest rates several more times.”

The ‘mortgage bomb’

When interest rates rise, a range of loans can get more expensive. More than 1.4 million people on tracker and variable rate mortgage deals usually see an immediate increase in their monthly payments.

The increase in the Bank rate to 4.75% from 4.5% would mean those on a typical tracker mortgage would pay about £24 more a month. Those on standard variable rate mortgages would face a £15 jump.

This comes on top of increases following the previous recent rate rises. Compared with pre-December 2021, average tracker mortgage customers would be paying about £441 more a month, and variable rate mortgage holders about £282 more.

If the rate goes up to 5%, those on a typical tracker mortgage would pay about £47 more a month. Those on standard variable rate mortgages would face a £30 jump.

Eight out of 10 mortgage customers hold a fixed-rate mortgage. Their monthly payments may not change immediately, but house buyers or anyone seeking to remortgage face a sharp rise in repayments when they move on to a new deal.

The so-called “mortgage bomb” has become a huge economic and political issue. An average two-year fixed deal, which was 2.29% in November 2021, is now above 6%.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), a politically independent economics-focused think tank, says rising interest rates could mean 1.4 million mortgage holders see their disposable incomes fall by more than 20%.

Renters are also feeling the impact. “It is likely that at least part of the increases in rents we are seeing is due to high interest rates hitting landlords’ borrowing costs,” the IFS said.

Rents have been growing faster than wages in the UK for nearly two years, according to exclusive data given to the BBC by property portal Zoopla.

Meanwhile, savers should benefit from a rise in interest rates, but MPs on the Treasury Committee have criticised banks and building societies for failing to pass this on in full to loyal savers who have instant-access savings accounts.