As a child growing up in Japan, things very rarely seemed to get more expensive.

My favourite lunch was always available for a 500 yen coin ($3.90; £3.10) and it remained that way until 2021. The same for shoes or clothes, little changed.

I was taught to save, save and save, and repeatedly warned that the value of our family home had collapsed in the 1990s, when the property market crashed.

This painful financial loss meant my parents, and many others like them, were never able to sell their house again or upgrade it.

But when prices for everyday items don’t increase, people don’t actively spend money.

Companies, in turn, respond by not increasing salaries, which lowers consumer demand and prices further. When you cannot get a pay rise, you don’t rush out to go shopping very often.

Taken altogether, this slows an entire country’s economic growth – a vicious cycle Japan has been trapped in for decades.

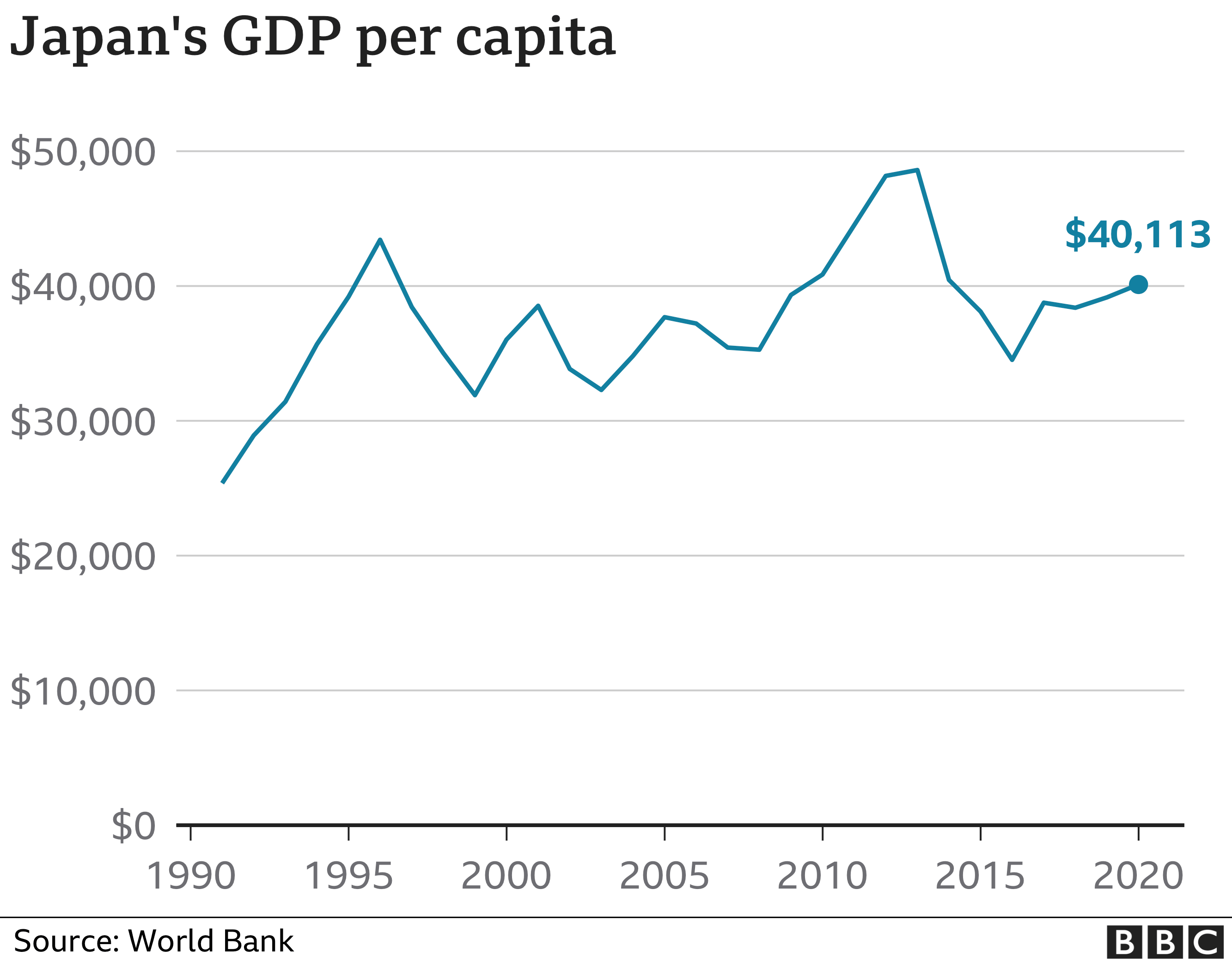

While many parts of Asia grew richer, Japan’s wealth stagnated. Japan’s gross domestic product per capita – the country’s economic output per person – remained stuck at the same level since the 1990s. By 2010, China had overtaken it as the world’s second-biggest economy.

For decades, with little success, the country’s central bank has tried to stimulate growth to get Japanese to “spend more, invest more, the wage goes up and the price goes up in tandem moderately”, explains Nobuko Kobayashi, a partner with EY-Parthenon.

In April, the benchmark measure for consumer prices rose 2.1%, enough that inflation this year is expected to finally hit the Bank of Japan’s 2% target, after three decades of essentially no rise at all.

However, the jump has nothing to do with domestic economic policy. It has been driven largely by higher import costs, a global increase in raw material and energy prices – pushed higher by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

Ms Kobayashi even warns it could mark “the start of bad inflation, because wages have not gone up yet”. In fact, average salaries have hardly risen for over three decades, so things are about to get painful for shoppers.

Japanese workers’ take-home pay has improved very little since the 1990s

Japanese workers’ take-home pay has improved very little since the 1990s

While post-Covid there are many governments battling rising prices and a higher cost of living, it comes as a huge shock to Japan, where people have been used to decades of stable prices.

When the price of Japan’s everyday snack – umaibo – which was always priced at 10 yen ($0.075; £0.06) since its creation 43 years ago – went up by 20%, it sent a shockwave through the nation.

In a society which believes in sharing social burdens, increasing prices has become something of a cultural taboo.

So much so that Yaokin, the company which makes the popular snack, had to launch an ad campaign explaining why it had to increase the price.

But it was inevitable and one by one, everything from mayonnaise and bottled drinks to beer has become more expensive. According to Teikoku databank, prices for more than 10,000 food items are set to go up by an average of 13% this year.

Central Bank dilemma

And here, Japan has a really tricky problem: central banks across the rest of the world have responded to soaring prices by incrementally raising interest rates to help keep inflation in check. The Bank of Japan has held rates at rock bottom for years.

If there is a significant gap in interest rates between Japan and other major economies, such as the US, the Japanese currency sharply weakens. The yen recently slid to 20-year-lows against the dollar.

A weaker yen means that imported items – crucially oil and gas – cost even more.

“Consumers are not accustomed to accepting inflation,” says Takeshi Niinami, who is the chief executive of Suntory Holdings, known for Japanese whiskies Yamazaki, Hibiki and Hakushu, as well as beer and non-alcoholic beverages such as bottled water and coffee.

The company has recently announced a price hike across most of its product range from October, to give itself time to discuss these increases with its distributors. Mr Niinami puts this down to the global supply chain crunch, caused by the pandemic and China’s recent lockdowns.

“Overall, it has been accepted. But there is still a challenge from big retailers,” he says.

Part of the rationale behind the government’s efforts to promote inflation in the Japanese economy has been to try to push wages higher.

“There’s huge pressure from society and the government to raise wages, but we need to increase productivity,” says Mr Niinami.

“But it’s difficult to increase productivity all of a sudden. We have so many peers in one industry, so we have to consolidate.”

Mr Niinami says Japan also needs to invest in new sectors such as green innovation or healthcare to stimulate the economy, and create new jobs to boost average salaries. He also hopes that the government will do more to attract foreign investors.

But all that will take time and job creation is just one of many issues Japan has been grappling with for decades.

The only silver lining of a weaker yen in the short term could be an influx of international tourists keen to spend their money in Japan, although the borders are only just starting to reopen after Covid.