From the outside it looks like an ordinary corporate building, lots of glass and steel, but this factory in the south of the Netherlands belongs to ASML, and the machines made there are anything but ordinary.

In fact, the technology is so advanced and so much in demand, that ASML has become Europe’s most valuable technology firm.

So what is made there?

ASML designs and makes the machines which make computer chips – but not any old computer chips.

ASML machines make the most advanced computer chips and it’s the only company in the world with that kind of technology.

This effective monopoly means that exactly how ASML’s machines work is subject to some of the most stringent corporate security in the world.

Nevertheless, we were given a tour of its plant, and were guided through the basics.

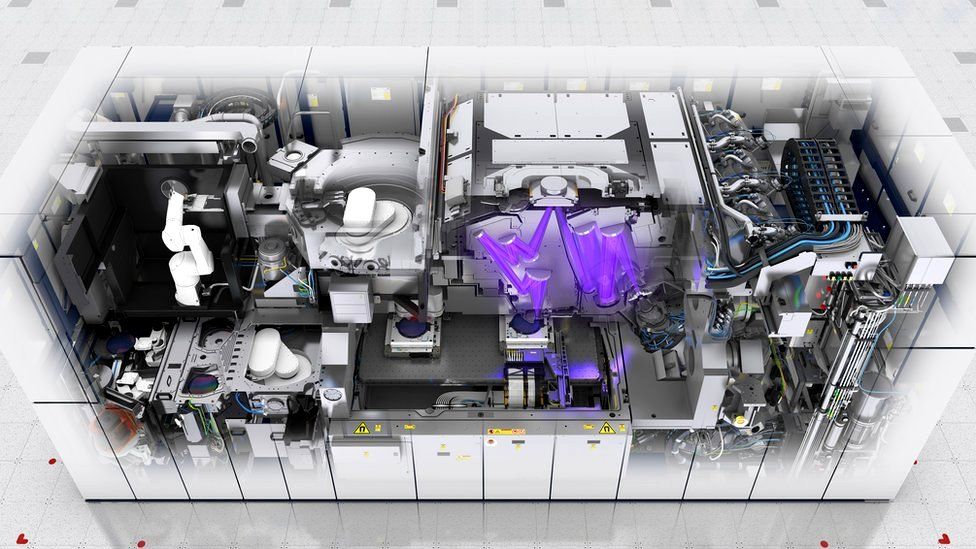

Microchips are made by building up complex patterns of transistors, or miniature electrical switches, layer by layer, on a silicon wafer.

They are printed using a lithography system, where light is projected through a blueprint of the pattern of those miniature switches.

The light is then shrunk and focussed using advanced optics and the pattern is etched onto a photosensitive silicon wafer.

That pattern forms the circuitry of a silicon chip, that might end up in a computer, phone or any other electrical device you might care to mention.

The crucial aspect of ASML’s most advanced machines is that they can work at tiny scales by generating super fine extreme ultraviolet light – just 13.5 nanometres.

Sander Hofman from ASML likens it to using pens with different tips: “Because of the small wavelength, that means that you basically are using a fine liner to draw these lines of integrated circuitry – instead of older generation machines which use maybe a marker pen.”

The ability to etch the silicon with such fine circuits means you can cram more components on to the silicon which, in turn, means electronic devices can have more processing power and more memory while remaining the same size.

The machines operate in a vacuum, as the whole process of etching a chip, can be derailed by the tiniest of impurities – like a rogue skin particle.

Technician, Bram Matthijssen was putting together one of ASML’s latest designs when we visited the factory. Mr Matthijssen works in one of the cleanest environments on the planet.

“There are moments where we have to wear gloves over gloves to make sure we don’t leave any finger prints, to make sure we don’t bring any extra dust into the machine.

“A single finger print… can cause significant damage to the machine,” he says.

The machines themselves are very substantial and complex. One extreme ultraviolet (EUV) machine can take a year to assemble and deliver.

Last year the company delivered only 50 of their highest specification model and 400 machines in total.

Those sales, plus income from the management and upgrading of existing machines, made the company 21.2bn euros ($22.7bn; £18.9bn) last year.

The orders they have in the pipeline are worth double that. The sales growth means a growing workforce, up by a third over the last 12 months.

Wayne Lam, a consultant with technology research firm CCS Insights, says the machines ASML make take years, if not decades, to develop and perfect.

ASML has been working on its highest specification machines since the early 2000’s, leaving other companies in the field with quite a bit of catching up to do.

“I’m sure there are competitors in the works… however, in the near term there isn’t any true competitor to ASML,” he says.

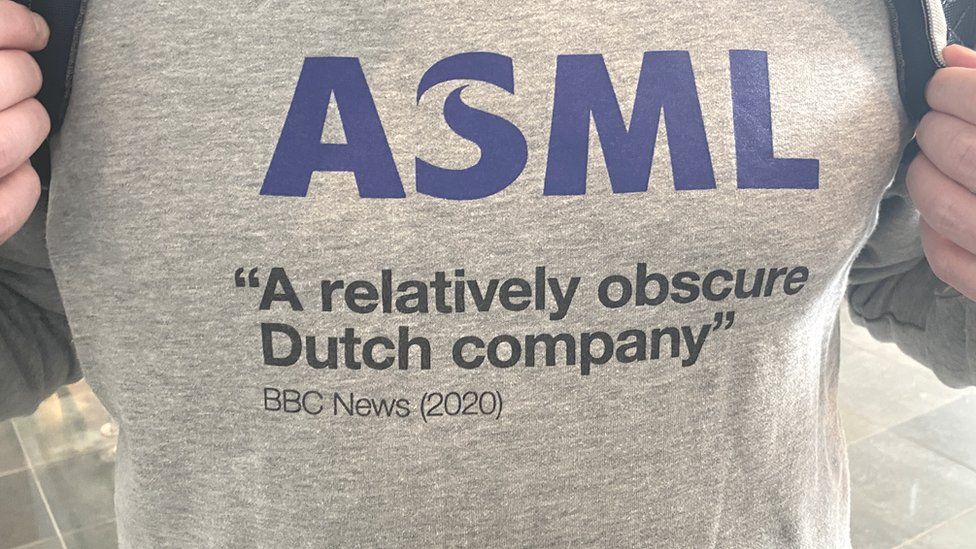

Not bad for a company once described by the BBC as “relatively obscure”, a quote which Mr Hofman has printed on a hoodie.

Being such a crucial cog in the global electronics industry comes with difficulties.

ASML currently finds itself caught in the rivalry between the US and China.

China has long wanted to make the most advanced computer chips, for which it needs ASML machines.

But since 2019, the US has effectively been blocking ASML from exporting those machines to China.

Joris Teer, a strategic analyst at The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies says the US is keen to prevent China from catching up in chip technology.

“The US have moved their goals, from having a couple of generations of an advantage on their rivals, to we must maintain as large a lead as possible – which can also mean you must put your rivals back as far as possible,” he says.